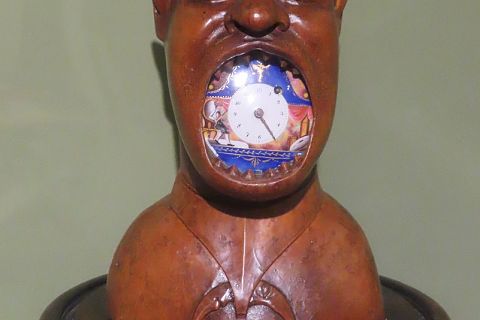

In commemoration of the victory over the Turks at Vienna in 1683, table clocks in the shape of a distorted Turkish head were allegedly crafted.

The Battle of Vienna, which took place on September 12, 1683, was a decisive military engagement between the Ottoman Empire and an allied coalition primarily made up of Poland, under the leadership of King Jan III Sobieski, and the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, along with German, Czech, and Hungarian forces. The Ottoman Grand Vizier, Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha, besieged Vienna with around 150,000 to 200,000 soldiers from July 1683, posing a serious threat to all of Central Europe.

The defenders of Vienna, consisting of imperial soldiers, Hungarian volunteers, and citizens, had little chance of success against such a larger Ottoman army. They had only about 15,000 soldiers defending all the city’s entrances, while the Ottoman forces were well-prepared. After eight weeks of siege, which led to severe hardship and near exhaustion of the defenders, news arrived of a relief force led by King Jan III Sobieski. Sobieski and his army, numbering around 70,000, crossed the Danube River and headed towards Vienna to break the siege.

On September 12, 1683, the decisive battle took place. Sobieski and his Polish hussars, known for their swift cavalry tactics and fearless attacks, struck the Ottoman lines from an unexpected angle, causing a massive break in the Ottoman military system. The allied forces began to attack the Ottoman troops, who were caught off guard and quickly retreated. Within hours, the Ottoman army was destroyed, with the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha fleeing the battlefield. Approximately 15,000 Ottoman soldiers were killed in the battle, while the allies lost around 3,500 men.

On September 12, 1683, the decisive battle took place. Sobieski and his Polish hussars, known for their swift cavalry tactics and fearless attacks, struck the Ottoman lines from an unexpected angle, causing a massive break in the Ottoman military system. The allied forces began to attack the Ottoman troops, who were caught off guard and quickly retreated. Within hours, the Ottoman army was destroyed, with the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha fleeing the battlefield. Approximately 15,000 Ottoman soldiers were killed in the battle, while the allies lost around 3,500 men.

The victory at Vienna had far-reaching political and military consequences. The Ottomans failed to achieve their ambitions of expanding westward, marking the beginning of the end of their expansion in Europe. After the battle, the allied forces, under Habsburg leadership, gradually began to reclaim territories held by the Ottomans in Central Europe, such as Hungary and Transylvania. The Battle of Vienna also marked the beginning of a long-awaited anti-Ottoman war, which continued for decades, eventually leading to the complete withdrawal of the Ottomans from Central Europe in the early 18th century.

In addition to the military victory, the battle had religious and cultural consequences. The victory was portrayed as the triumph of Christian Europe over Islamic imperialism. In gratitude for the victory, the allied forces, especially the Poles, received numerous honors and valuable spoils. A church was built at Kahlenberg Hill in Vienna to commemorate this victory, and Sobieski’s decisive role in the fight against the Ottomans was recognized. Pope Innocent XI bestowed the title “Defender of the Faith” upon King Jan III Sobieski, a great honor and recognition for his role in protecting Europe.

The legacy of this victory also manifested in other fields. For example, the astronomer Johannes Hevelius named the constellation Scutum after King Jan III Sobieski. On the musical front, composers wrote several pieces in honor of the victory, and folk songs about the triumph over the Turks (including Slovenian ones) were created and preserved. There are also various culinary stories linked to this victory. It is believed that the legendary croissant was invented in Vienna after earlier Turkish sieges in the 16th century, as its shape resembled the crescent moon on Ottoman flags. An even more famous story tells of coffee bags that were discovered by Viennese in an abandoned Ottoman camp, and that Frančišek Jurij Kulczycki was the first to serve coffee in his Viennese café. Another, more likely story is that the captured coffee was mixed with sugar and foamed milk to create the drink we now call cappuccino. The name was likely derived from the Capuchin friar Marco d’Aviano, who encouraged Catholic forces to unite and defend Vienna.

Among the citizens, various souvenirs from the great victory became highly fashionable, ranging from Turkish horseshoes and tent products to table clocks with Turkish heads. According to Niko Sadnikar, from whose family collection the Kamnik museum acquired a clock, such clocks with distorted Turkish heads and a crescent moon were very popular.

Sources:

Wikipedia: The Second Siege of Vienna

Wikisource: The Turks at Vienna in 1683

Informant Niko Sadnikar, Kamnik

Zora Torkar